(read the first part)

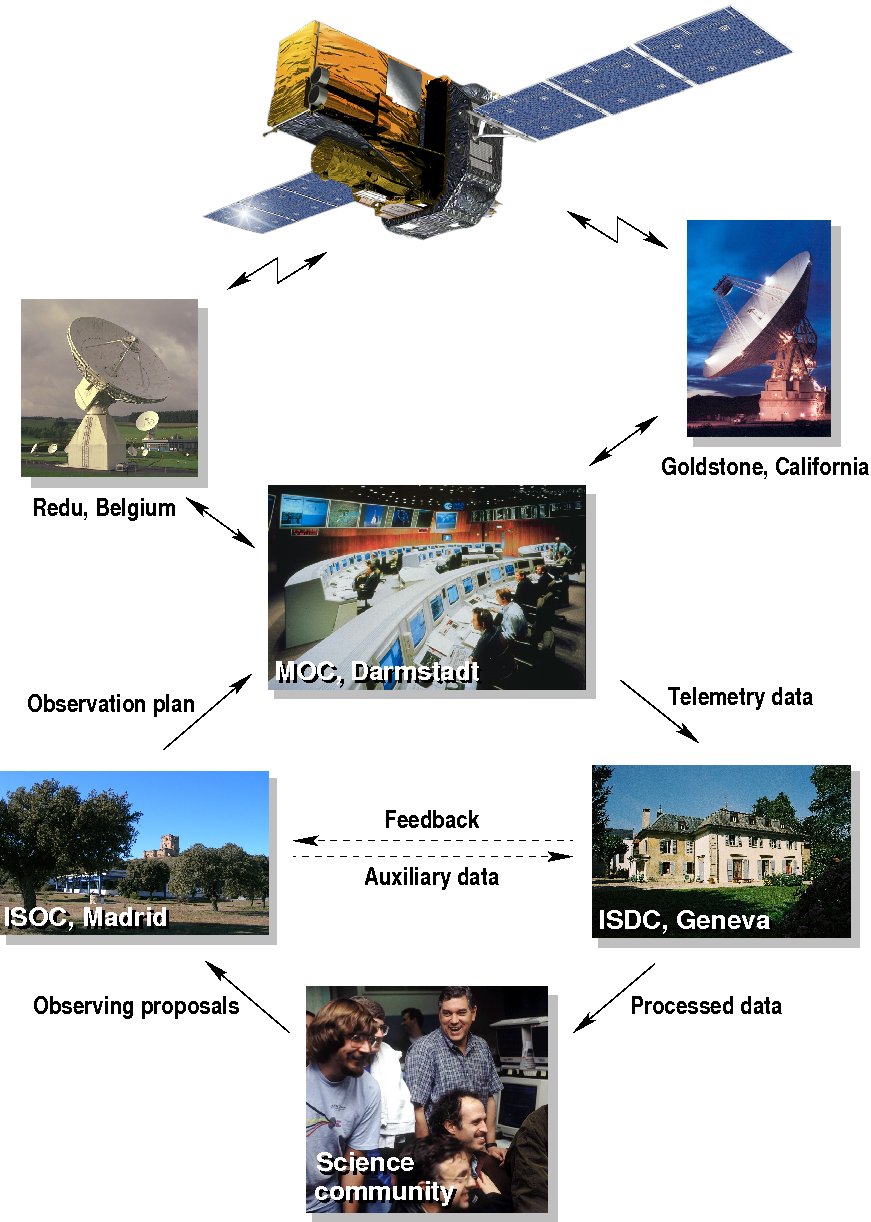

On October 17th, 2002, the European Space Agency satellite INTEGRAL (INTErnational Gamma Ray Astrophysics Laboratory) was launched. Its telemetry began to flow continuously to the INTEGRAL Science Data Center (ISDC) in Geneva, where I had already spent almost three years.

The arrival of the real data, after so much work with simulations, was surreal: the satellite was really in Space observing the Universe in X-rays and gamma rays. And it was speaking to us.

The years I had spent testing the INTEGRAL data analysis software proved very useful. In a short time, I found myself working with many scientific collaborations which were new to the coded mask approach and very happy to have me on board. Those years were hugely exciting for me, even – dare I say – epic. I had the pleasure and honour of working with people from various parts of the world, and opportunities to travel to the United States and Japan, via Europe.

But I wasn’t alone. One of the most exciting, humbling and educating aspects of such a scientific mission is the community: you just can’t make it alone. Neither as a person, nor as a country. (And I am not even sure it is worth trying to do so). In addition to the constant support from my coordinators – Thierry Courvoisier in Geneva and Sandro Mereghetti from Milan – I remember the intense dialogue with Diego Götz (in Milan, who was growing with me from a scientific point of view) and Pascal Favre (ditto, in Geneva), as well as the fundamental help of the ISDC scientific staff who were more experienced than me, including Jérôme Rodriguez, Ken Ebisawa and Volker Beckmann. Honorable mentions also to the new recruits, who arrived long after me (my turn to be senior!), including Simona Soldi. Not to mention the powerful software group of the ISDC that helped me deal with the metaphysical error messages that the software would inflict on me. And many, many other people that I simply don’t have the space to name here.

Of course, it wasn’t all plain sailing: there were moments of tension and even less than thrilling work duties, but I expected them. What I didn’t expect, however, was to arrive at work for my shift as scientist on duty a month after the launch, on the morning of November 26th, 2002, analyze the data from the previous hours, and discover that a new source had lit the sky.

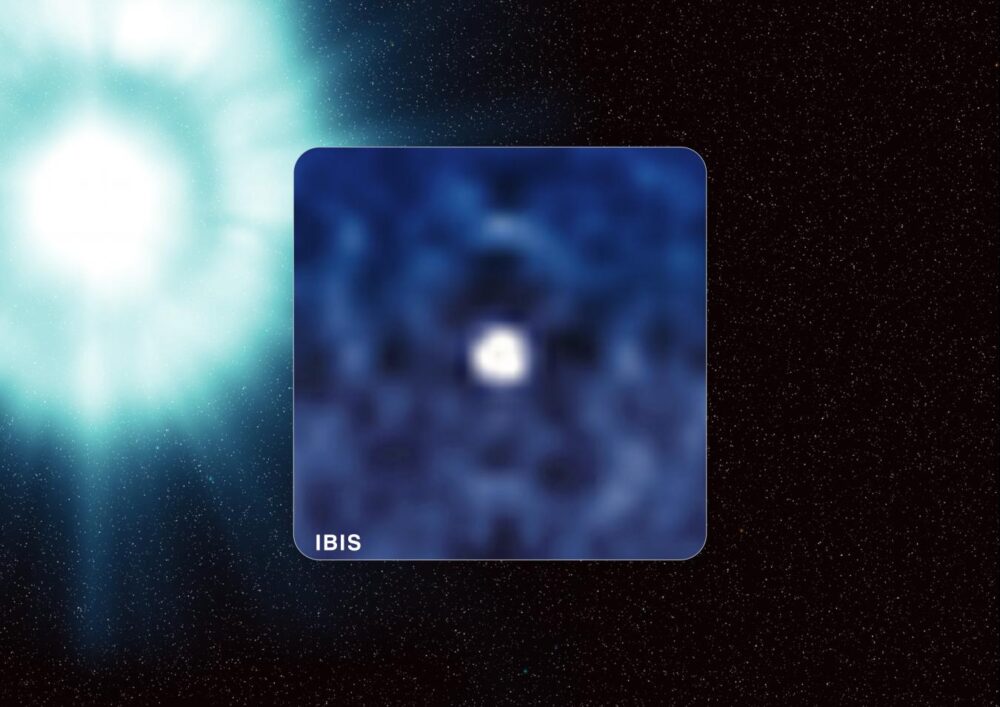

My first thought was that I had made a mistake in my analysis. Was it possible that so soon in the early stages of the mission, even before the nominal observations (with me on duty at the ISDC!) a new source was born in the sky? I repeated the analysis several times, finding the same result. There was no doubt, it was real. It was an event about twenty seconds long but so bright that it had obscured everything else, leaving a clear shadow of the mask on the IBIS detector, as if there were no other sources in the sky to contribute with their own. It proved to be a gamma-ray burst, later called GRB021125 (GRB for Gamma Ray Burst and the date of detection). The event had also been identified by the IBIS instrumental group independently. It was the first GRB seen by INTEGRAL in the field of view of one of its instruments and it was my first impact with something new in the sky. And I was among the first people in the world to see it(1)Shortly after, with the arrival of nominal observations, the INTEGRAL Burst Alert System (IBAS, managed by Sandro Mereghetti and Diego Götz with the technical collaboration of Jurek Borkowski), a system for the real-time detection of GRBs in the IBIS field of view, became operational..

During my years in Geneva I had other exciting “first times” like this one, as well as some more thoughtful ones. One day, during a consortium meeting at the ISDC, I heard the words I have been waiting for this observation for ten years. I stared at the imputed image that was proudly displayed, I looked around, and I sensed that something important was happening, but I did not understand what: to my eyes that image, which I now would not even be able to identify, was quite standard, an image like any other from INTEGRAL.

From INTEGRAL!

Afterwards I understood: if my story with this satellite had begun towards the end of 1999, the story of the people involved was much longer. It came from previous, historic, decade-long missions, which had served as fertile ground for INTEGRAL (which in turn had been proposed to ESA way back in 1989 – this is the timeline in research). I had only been there for a few years and I could not understand the emotion of those who were finally seeing the gamma-ray sky with those eyes. I was missing out on history and the wealth of emotions it can bring.

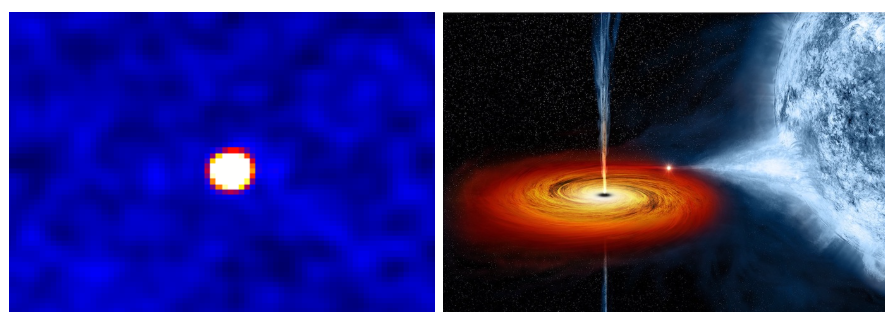

During my PhD, while continuing the operational activities for the ISDC, I began to get passionate about X-ray binaries, a type of binary system with a strong emission in X-rays, formed by a star (with nuclear reactions at its center, like the Sun) and a second, more exotic object: a neutron star or a black hole.

The image on the left above shows what we typically observe with INTEGRAL in hard X/gamma rays, in the case of a point source (here a binary system). The image on the right is what we think is a possible representation of it.

There is no denying that there is a lot of creativity in science.

The distance-size combination of many celestial objects, together with the technological challenge of imaging X and gamma rays, does not allow us to see the sources in detail, and this is where the fun begins. We start observing a celestial object with multiple satellites in different energy bands, and extract as much knowledge as possible with the use of various tools, such as: images (distribution of photons in space), spectra (in energy) and light curves and the like (in time).

We then imagine a plausible scenario for what we observed and, finally, we turn to our queen of the sciences to amalgamate everything: Physics.

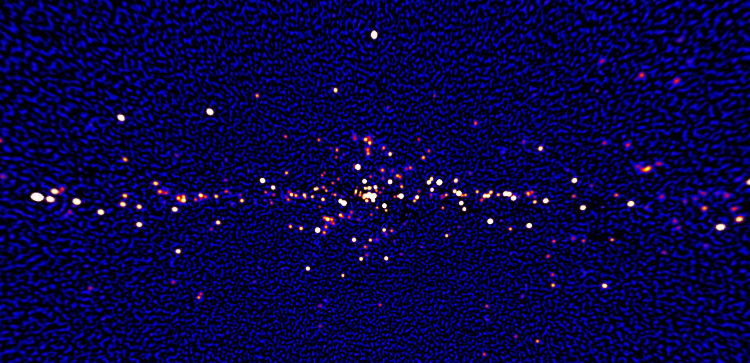

Hence, over the years, with the contribution of the entire scientific community and thanks to Ground – Space coordinated observations, INTEGRAL has allowed us to explore a great wealth of cosmic phenomena and domains of Physics. For example, it has discovered and identified about a thousand sources, including hundreds of active galactic nuclei and new classes of binary systems (including Supergiant Fast X-ray Transients, SFXT). It has discovered and studied more than 150 GRBs in the IBIS field of view thanks to the INTEGRAL Burst Alert System (IBAS); it has traced the diffuse emission of the Milky Way, creating a detailed map of the nucleosynthesis processes and the 511 keV emission due to electron-positron annihilation at the center of the Galaxy. And much more.

INTEGRAL‘s legacy is not limited to the scientific areas for which it was designed and built, it also covers topics such as gravitational waves and ultra-energetic neutrinos, milestones of multi-messenger astrophysics.

At one point, INTEGRAL even literally started to flip to continue observing the Universe.

The topics I mention above are the tip of the iceberg of the thousands of publications, archives or selection of results obtained by scientists around the world during more than twenty years of operations. But there’s more: in my opinion, the legacy of INTEGRAL, and in general of scientific missions, has roots much deeper than the list of publications, individual discoveries or archives available over time. It involves collective awareness and growth.

Even though, looking at the world, you sometimes wouldn’t say so.

To conclude this journey, I would like to be able to give voice to the entire INTEGRAL community but, for obvious reasons, I can’t. I will limit myself to some of the people whose paths have long intertwined with mine. I asked them to share a short personal thought on INTEGRAL. Here’s what they told me.

In their own words

Sandro Mereghetti, Research Director at INAF-IASF in Milan:

Although the instruments were designed to provide a great improvement in sensitivity, energy resolution, and angular resolution, INTEGRAL was not born with the primary goal of studying gamma-ray bursts. In those years it had become clear that to solve the mystery of gamma-ray bursts it was crucial to obtain their positions with the highest accuracy and in the shortest possible time. The IBIS instrument was able to do this, but unfortunately the onboard computer did not have the computing power necessary for this complicated analysis. So we proposed to search for and localize the gamma-ray bursts with a software that immediately examined the data as soon as it was received on the ground (the aforementioned IBAS project, author’s note). In this way, in exchange for a small time delay, we could use much more efficient algorithms and INTEGRAL was the first gamma-ray telescope to provide positions with the precision of a few arcminutes in a few seconds for gamma-ray bursts and other transients such as magnetars. I think this was my most important contribution to INTEGRAL.

Thierry Courvoisier, Honorary Professor University of Geneva:

Creating and developing the ISDC, INTEGRAL Science Data Centre, was an endless battle to obtain support in Switzerland and abroad. We needed to build a team from scratch to develop software and infrastructure. This was a human adventure, people came from all horizons and were to work together. Organising life so that all could be comfortable and give their best in an environment not originally meant for science was the name of the game. It took 10 years. We were ready at launch. Thanks to all.

Diego Götz, Research Director at Département d’Astrophysique of CEA Saclay France:

INTEGRAL represented for me a formidable opportunity for professional growth: I started working on INTEGRAL during my thesis at the (then) Institute of Cosmic Physics in Milan (today INAF IASF in Milan, note of the Author). I worked on it starting a little more than a year before launch, just when the wait for the first data was starting to become palpable, but also the tension to have all the software ready for the launch was starting to become important. Fortunately, the launch was a success and we were able to immediately collect the first scientific results, already during my doctorate. Even the first years of postdoc were dedicated to INTEGRAL and this continuity allowed me to acquire good skills in both the instrumental and physical fields.

But INTEGRAL for me was also a great human adventure: the fact that it was a large international collaboration allowed me to meet researchers from different nations and cultures, to easily get in touch with people I had only heard about in books or articles, thanks to the fact that INTEGRAL was the main mission in its field at that time. I think that this international openness later favored my career, thanks to the contacts that I was able to cultivate during the first years and that I don’t think I could have obtained in a project of less broad scope,

Jérôme Rodriguez, today Research director at the department of Astrophysics CEA, Saclay France, and deputy director of doctoral school astronomy and astrophysics Ile de France:

I had just finished my PhD when INTEGRAL was launched in 2002. Until March 2025, it has accompanied me through more than 22 years of my career as a dear old friend: always there no matter what. INTEGRAL observations have given me everything: the thrill of being the first to see something new, the excitement of scientific progress on my favourite celestial objects, and a career. Analysing real-time data to know what the transient sky was doing was my rock-solid routine that I would start my day with. Perhaps more importantly, INTEGRAL allowed me to meet extraordinary people, some of whom have been dear friends for more than 20 years.

Salute buddy, may you now rest in peace with a sense of great accomplishment.

Volker Beckmann, today at the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research:

INTEGRAL was a really complex experiment from the point of view of data analysis. Surprisingly, this offered to us young researchers at the time an excellent opportunity: those colleagues not familiar with INTEGRAL and who used the telescope to observe their favourite objects in the sky were often frustrated, because they couldn’t make sense of the data. This opened the way for us, who spent a lot of time in order to get the most out of the observations. And thus we developed quickly into experts in this field, and because of our expertise we got exposed to a lot of different topics. I worked on INTEGRAL data from supermassive black holes, binary stars, gamma-ray bursts, super nova remnants… Where would one get otherwise such a wide field of astrophysics to work on?

Lara Sidoli, with whom I collaborated for a long time since my return to Italy in 2005, when I developed the INTEGRAL archive for our Institute – echoes of ISDC in Milan. Today Lara is a senior researcher at INAF IASF in Milan:

When in 2001 I happened to see the INTEGRAL satellite kept at ESA/ESTEC, in the Netherlands, to be fine-tuned before launch, I could never have imagined the decisive influence that INTEGRAL would have had on my personal and professional life in the years to come. From a professional point of view, thanks to its observations I was able to discover the first orbital period of a SFXT, at a time when we were groping in the dark in front of this new class of binary systems discovered thanks to INTEGRAL. It is thanks to a fixed-term contract financed by INTEGRAL funds that I was able to return to work in Italy after a period of work abroad. It is thanks to the community of scientists who worked on INTEGRAL data that I grew professionally and personally, and some of them became important friends. And it is with gratitude and emotion that I welcomed the end of INTEGRAL’s operations, for all this space mission has unexpectedly brought into my life.

I refer here for a comment by Pietro Ubertini, principal investigator of IBIS and promoter, together with Angela Bazzano, of the economic stability of a large group of young scientists with time limited contract, including myself from 1999 to 2010, the year in which I became a tenured researcher.

It will take years to explore every single piece of data from INTEGRAL, the archive is vast. But in the meantime, since March 4, 2025, after more than 22 years (8174 days) in orbit, INTEGRAL no longer speaks to us.

INTEGRAL was my first mission. I was there when it opened its eyes to the Universe, it was there when I opened mine to science. I will never have another mission with such an impact in my life, and I feel a bit like I’ve lost a friend. Today I am senior researcher at INAF IASF in Milan and I deal with scientific outreach and communication. I owe a large part of who I am to INTEGRAL and to the people I have met along the way, those who are still here and those who are no longer with us.

And I thank them all.

When INTEGRAL re-enters the atmosphere in early 2029, we will look up – with a collective gaze – to search for that shooting star that has so intimately been part of us.

Thanks, INTEGRAL, for piercing through the dust to reveal a universe full of bright, but paradoxically hidden, objects.

And thank you, Ada, for capturing the excitement of those early years of discovery. As Jerome and you said, the ISDC post-launch was a special place and time; not only for fruitful collaborations but also for enduring friendships.

I worked on this project from 2000 to early 2009, mainly as a developer of the instrument specific software of IBIS/PICsIT, and it was crucial to get the permanent position at INAF. Those were extremely hard and hectic years, which I could overcome thanks to the help, kindness, and warmth of many colleagues, in particular Guido Di Cocco, Andrea Goldwurm, Aleksandra Gros, Thierry Courvoisier, Nicolas Produit, Ada herself, Jerome Rodriguez (with whom I shared the office at ISDC) and many, many others that I do not mention only for space reasons. I am lucky and honored to have known them, and I am a little sad that our lives took us in different directions. I can never thank them enough for their help in those difficult times.