Aggiornato il 7 Maggio 2025

On March 4th, 2025, the INTEGRAL satellite (INTERnational Gamma Ray Astrophysical Laboratory) showed us the Universe for the last time.

Launched on October 17th, 2002, the European Space Agency satellite, with contributions from the United States and Russia, operated for more than twenty years – quite an age for a satellite, considering that it had initially been meant for just two. INTEGRAL has provided discoveries, emotions and new eyes on extreme phenomena such as black holes, supernova explosions and gamma ray bursts.

But for me, it has given me so much more: INTEGRAL was my first scientific mission, and I would like to share my personal notes(1)To learn more:

INTEGRAL latest news (ESA)

INTEGRAL videos (ESA)

INTEGRAL website (ESA)

INTEGRAL picture of the month (ESA)

The INTEGRAL Science Data Center (ISDC)

INTEGRAL at INAF IASF Milan.

In 1999, after completing my Master of Science in Physics from the University of Milan at the age of 26, I won a research grant under the direction of Sandro Mereghetti of the INAF IASF of Milan (then part of the CNR), to work at the INTEGRAL Science Data Center (ISDC) in Geneva.

New job, new house, new panic.

The ISDC was created to receive the raw data (the telemetry) of the satellite, perform a quick look analysis in search of cosmic events that required immediate attention, and provide the scientific community with the processed data, as well as the software for the scientific analysis. People from several countries came together to form an international scientific community within the ISDC and collaborated successfully with external scientists (e.g. the instrument developers), with a common goal: to ensure the success of the mission.

INTEGRAL was designed to study the Universe in X-rays and gamma rays, the most energetic part of the electromagnetic spectrum. The Earth’s atmosphere absorbs this radiation, which does not reach the ground. Therefore, it is necessary to go into Space to detect it.

Other satellites had already observed the sky at such high energies, but INTEGRAL was among the first to do so with special eyes, taking the best specifications from those which had preceded it: large field of view (more than 900 square degrees), wide energy coverage in X-rays/gamma rays (3 keV – 10 MeV) and the ability to distinguish nearby events in in space, time and energy.

INTEGRAL had new eyes and in my own way, I had to follow suit so as to focus on my days as soon as I arrived in Geneva in early 2000. The impact was immediate and powerful: an international scientific community that had been active for much longer than me, mostly incomprehensible meetings, new faces, a chain of deadlines … how was I to fit in?

With essential feedback from Milan and among all the possible activities before the launch of the satellite, I decided to dedicate myself to the INTEGRAL Observation Simulator (OSIM) – developed by the collaboration and on which Davide Cremonesi and Sandro Mereghetti were already working. The importance of a simulator is easily explained: although the scientific data from a satellite arrives only once it is up and running in orbit, the data analysis software has to be ready. And how is it prepared? With another code that creates data very similar to real data, the simulator.

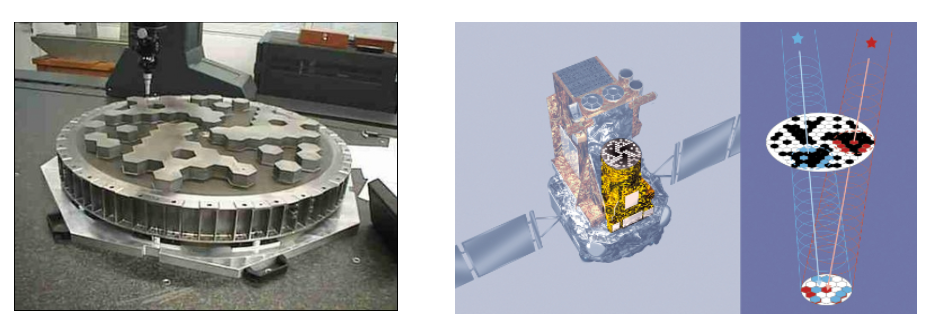

This is because INTEGRAL had a very peculiar characteristic. Unlike visible radiation, the most energetic X-rays (called ‘hard’) and gamma rays do not even notice the presence of traditional mirrors. They simply pass through(2)For the curious ones: the X-rays observed by INTEGRAL are called ‘hard’ X-rays because they reach up to tens of keV – kiloelectronvolts. Other missions that study the so-called ‘soft’ X-rays (around a few keV, such as XMM-Newton or Chandra), are capable to focus the radiation via the grazing incidence optics. This is not possible for hard X-rays or, worse, gamma rays, in which INTEGRAL observes, which are even more energetic.. In order to create an image, it is therefore necessary to use a technique that involves something more substantial: a coded mask, blocks of material such as tungsten (alternating with empty spaces) which stop the radiation when placed over the detector.

Each source creates its own image (shadow) on the detector through the mask. Starting from the mosaic of shadows and knowing the structure of the mask, it is possible to trace back the position of the individual sources in the sky.

This was a revolution for most of the scientific community, who was accustomed to dealing with data from traditional focussing mirrors, where two sources far apart do not overlap on the detector. Moreover, you can consider a source-free portion of sky, in the surroundings of the sources, to have an estimate of the background. In contrast, this is absolutely forbidden in coded mask instruments: each source leaves its own image on the detector, which then mixes in with all the others. Therefore, each source interferes with the others and only the analysis code is able to estimate the background.

It may seem like a nerdy detail, but it is like having to drive on the left in London after years of driving on the right in Milan (it was not like that for me: INTEGRAL was my first mission, to me everything seemed normal – ignorance is bliss).

Three of the four instruments on board INTEGRAL had coded mask instruments: IBIS (optimized for gamma-ray imaging), SPI (optimized for spectra in the same band) and JEM-X which observed the sources at the lowest energies (so to speak: we are still in the hard X-rays). Finally, for a more complete view of the sources (what is called multiwavelength observation), there was also a camera for visible light, OMC.

INTEGRAL is quite a masterpiece: 5 meters high, 16 meters wide, once solar panels are deployed, and a weight of almost four tons, to simultaneously observe the sky in multiple energy bands. The point is, if you have to go through the trouble of launching a satellite, you had better optimize it. This approach is common to all satellites.

My years of preparation for the launch were an adrenaline high. The idea of being part of a community that aspired to touch the sky excited me every morning, evening, every simulation run, handshake, meeting, bug found in the software, new friendship, dry mouth before the consortium meetings, party to celebrate the success of talks, international cooking scents in the ISDC kitchen, and much more.

Due to some strange time dilation, the beginning of the adventure felt somewhat slow, perhaps due to the difficulties that marked my days – but then as I gradually gained confidence and the launch date approached, everything began to accelerate until one day, suddenly, everything took off.

October 17th, 2002, dawn. We arrive at the ISDC to watch the launch live from Baikonur, in Kazakhstan. Guests and collaborators from around the world are visiting and we, the “locals”, are in a good-host frenzy mode. In the meantime, I had started my PhD in astrophysics with Thierry Courvoiser, the Director of the ISDC. There were other PhD students with me, including Pascal Favre, from Switzerland. Thierry had decided that the PhD students would receive updates of the most important launch steps by phone, and then pass them on to him on a paper note. In turn, he would gradually update the audience.

The moment of launch arrives: the first seconds seem flawless. Then I get a shock because the transition to supersonic speed looks like an explosion. But it is not: the Russian rocket, Proton, does not miss a beat and keeps going, with INTEGRAL in the tip(3)INTEGRAL launch video here..

Proton disappears from our view and soon the phone calls begin. I remember the one Pascal answered in particular. He listens, nods, nods, listens. He hangs up and says in a very controlled voice that there seems to be a problem with the opening of the solar panels.

No panels, no mission.

Apnea.

Another phone call: Pascal answers. Similar scene. He hangs up and tells us that everything is fine: the panels are deployed.

INTEGRAL is breathing!

I do not want to encourage the stereotype of the cool-headed Swiss under control and the warm-blooded Mediterranean (Italian-Greek) out of her mind, but I have often imagined the scene in which I was the one receiving the news about the solar panels on the phone. Forget about aplomb and paper notes…

But it was done, INTEGRAL was in Space: a new phase of our journey was beginning.

(read the second part)

Note

| ↑1 | To learn more: INTEGRAL latest news (ESA) INTEGRAL videos (ESA) INTEGRAL website (ESA) INTEGRAL picture of the month (ESA) The INTEGRAL Science Data Center (ISDC) INTEGRAL at INAF IASF Milan |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For the curious ones: the X-rays observed by INTEGRAL are called ‘hard’ X-rays because they reach up to tens of keV – kiloelectronvolts. Other missions that study the so-called ‘soft’ X-rays (around a few keV, such as XMM-Newton or Chandra), are capable to focus the radiation via the grazing incidence optics. This is not possible for hard X-rays or, worse, gamma rays, in which INTEGRAL observes, which are even more energetic. |

| ↑3 | INTEGRAL launch video here. |

Add Comment