Welcome back for the last Universe World column of 2024. This month, we travel to South Africa, where we meet Ramasamy Venugopal, operations manager at the International Astronomical Union’s Office of Astronomy for Development (IAU OAD). Based in Cape Town, the IAU OAD aims to further the use of astronomy, including its practitioners, skills and infrastructures, as a tool for sustainable development globally.

I have always loved astronomy, but I did not choose it initially as a career path. I studied to be a telecommunications engineer and worked in the industry for a few years. Eventually, I decided to do a masters degree. While researching for suitable programs, I chanced upon an opportunity that took me in a very different direction. Instead of telecoms, I enrolled in an interdisciplinary, masters degree in space science and technology, specially designed for those from engineering backgrounds such as myself. I got lucky when I discovered the IAU OAD fellowship program a few days before graduation. I emailed a project idea to the OAD, and a few months later, I ended up in South Africa!

What is your role at the International Astronomical Union’s Office of Astronomy for Development?

I manage the IAU OAD operations and projects. I coordinate our global grants program which involves designing and setting up the call for proposals, coordinating the applications and review process, and thereafter, overseeing the projects that we support. It also involves educating the community and supporting people in turning their idea into a proposal. Once projects are selected, I work with them to ensure they are on track to achieve their deliverables and outcomes, and lead our impact measurement process.

Let’s take a step back. What is astronomy for development?

The idea that discovery science, such as astronomy, should directly benefit us is not a universally accepted one. I have heard different opinions, from both within astronomy and outside, on the role and purpose of astronomy and astrophysics research. One argument is that pursuing curiosity-driven, discovery science is human nature, and part of what makes us human. And that expecting astronomy to solve everyday problems defeats the purpose of curiosity-driven science. On the other hand, astronomy (and other discovery sciences) cannot be apart from the rest of the world. Astronomy is so deeply ingrained in our cultures that it presents an undeniable opportunity to leverage it for good.

My opinion is that, in the end, we need a bit of both. Given our current state of the world, astronomy is one of the few global, inspiring forces that deeply affects all of humanity. Astronomy for development is simply taking advantage of this ‘power’ of astronomy to direct it towards creating positive, sustainable change.

What kind of projects does the OAD support?

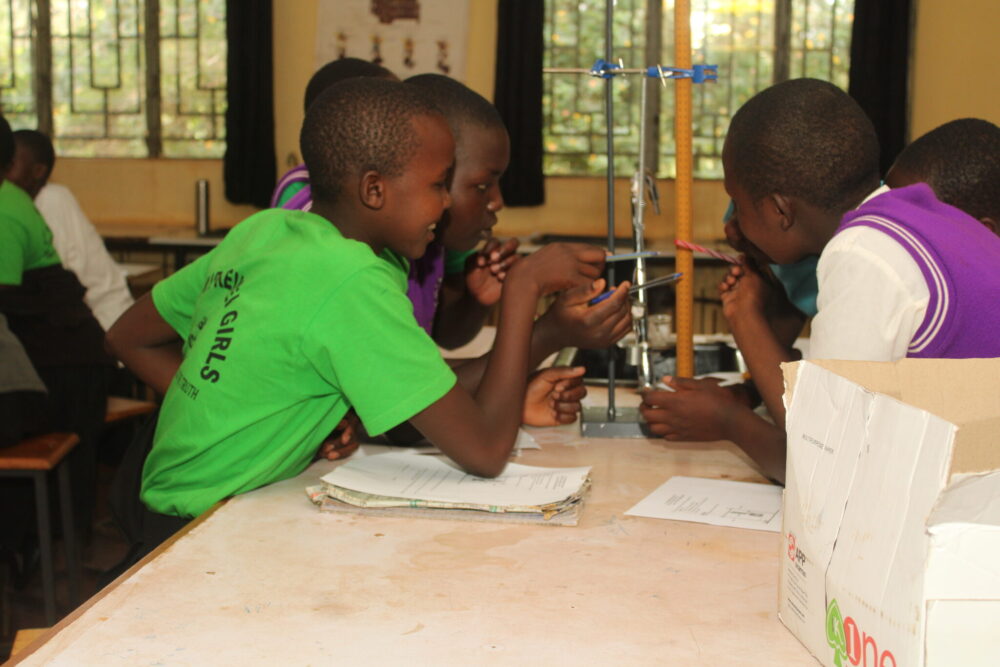

The IAU OAD applies a broad definition of astronomy for development in order to encourage innovative projects. We have thus supported a diverse collection of projects, from educational initiatives that use astronomy to inspire students to follow STEM careers or change attitudes, tourism projects where rural communities and astronomy observatories leverage the public fascination for astronomy into economic growth, stargazing and nature-based experiences to improve mental well-being, capacity building programs at schools and universities, and others. Since projects are meant to solve complex real-world issues, it is imperative that they are run by multidisciplinary teams, and not solely driven by astronomy. For instance, some of our projects working with vulnerable audiences in refugee camps collaborated with psychologists and experienced experts who offered counselling and support before the astronomy intervention.

Tell us about some specific projects the office has supported in the past few years…

Some of the most interesting and impactful projects that the OAD has supported have all involved strong collaborations outside astronomy. All of them spent considerable effort to understand their problem context and weren’t afraid to be creative in the application of astronomy for development. In Cyprus, for example, the Columba-Hypatia: Astronomy for peace project used astronomy as a tool for promoting meaningful communication between the various communities living on the divided island. In India, Astrostays is a combination of “astronomy” and “homestays” that leverages the human fascination towards astronomy and space for sustainable livelihood, engaging tourists in astronomy, local culture, stories and heritage while living in a homestay. In Kenya, EMEJA aims to address issues such as early marriages, teenage pregnancies & poverty, schoolgirl dropout rates in rural areas of Kenya & Uganda.

Astronomy for development (astro4dev) also includes, but is not limited to, outreach and education projects. How do these three activities interact with one another?

We always use the phrase that “astronomy for development is about people, not the stars”. While outreach and education activities focus on engagement and teaching of astronomy, astro4dev uses astronomy as a tool, not an end goal. Outreach and education projects play a major role in astro4dev due to their broad appeal and reach, and the massive global network of volunteers running such projects. Astro4dev projects may implement outreach and education activities, but with a goal of development, and not simply to engage or educate.

In practice, it means the astro4dev project design has to be centred on a development goal with the outreach or educational activity as the medium.

How do you engage with the broader astronomy community around the world?

Thanks to well-established outreach, education, and amateur communities in astronomy, the OAD has been able to count on passionate people around the globe. Over the years, we have built a great group of volunteers, Regional Offices, and collaborators, who have created lasting impact through projects. In addition to regular communication with our global network, the OAD engages astronomers and students at various conferences. We work with the other IAU Offices and Centre, taking advantage of our geographic spread, to promote each other’s work around the world.

And in practice? How does a typical day as IAU OAD operations manager work for you?

A large part of my work revolves around coordinating our call for proposals, and managing the projects that we support. So a typical day involves some work related to the application process and/or project coordination. Depending on the time of year, it includes preparing and issuing the call, supporting applicants, and coordinating evaluations. Once the outcomes of the proposal process are final, my role then transitions to collaborating with the project teams, monitoring progress, and offering any other non-financial support.

The other part of my work relates to communications and event management. Until recently, I was chair of the IAU’s Communicating astronomy with the public conference group, which organises the international CAP conference. I was also recently part of the team that organised the 32nd IAU General Assembly.

Indeed, South Africa recently hosted the IAU General Assembly in Cape Town, the first on the African continent. Can you tell us more about the impact of this event on the local – and global – scale?

The recently concluded IAU GA turned out to be one of the most enjoyable and productive conferences I have attended or organised. It was attended by 2000 in person and 600 virtual participants from 107 countries, including 28 African nations. There were 211 science sessions and 16 poster sessions – all fully hybrid. For the first time at an IAU GA, we employed an immersive platform as well as Slack and all sessions were streamed live on Youtube! It was the first event to run a fully hybrid poster session, a live radio broadcast, a live link to the International Space Station, an on-site local handicraft market. An extensive outreach and education programme reached around 28,000 school learners, 85 educators and 3,800 members of the general public, mainly in Cape Town.

Apart from the scientific impact on astronomers and students, especially those from Africa who are unable to participate in many major conferences, the IAU GA left an indelible impact on students and public, as well as economically benefited entrepreneurs and small businesses. And it pushed the boundaries of hybrid conferencing, challenging traditional ways of working and testing new solutions. I hope that future conferences are able to learn from our experience and further improve the hybrid participant experience.

How much work was involved in this impressive endeavour?

Enough work to give sleepless nights to quite a few people! We had a national organising committee in charge of the arrangements, assisted by a large group of volunteers. Several organisations from South Africa and abroad were involved in organising the conference. The planning was a multi-year process that began in 2018 after the announcement of South Africa as the next host. So it was incredible to see the efforts of everyone involved come to fruition during the two weeks of the GA.

During the IAU OAD day at the general assembly, you quoted astronomy professor and OAD co-founder George Miley, reminding the community that research institutions should commit to funding for development projects, investing at least 3% of their budget in astronomy for development projects. Do you think we are on the right track to achieve this objective?

Unfortunately, most research institutions around the world are publicly funded, leaving them open to the vagaries of political decisions. Research and education funding are typically the first to bear the brunt of budget cuts in government. Highly developed countries spend 2-4% of GDP on R&D, but there are only a handful of nations investing in research at this level. If we are to invest a portion of research funding to science-for-development, we need to commit a bigger slice to research overall. But in the meantime, there is plenty of opportunity to leverage existing infrastructure, people, and other resources at research institutions in the cause of development projects.

You have been working in South Africa for several years and you are originally from India. Both countries have a sizeable and growing astronomy community. What are the major issues for astronomy in these two countries?

South Africa and India go back a long way in terms of shared histories. They are both very diverse countries with not dissimilar socio-economic challenges. Interestingly, both countries took the leap in the early days of democracy to invest in astronomy.

South African astronomy has grown tremendously in the last couple of decades. South Africa works closely with multiple partners across Africa, supporting them in developing their own astronomy programs. Building local capacity is a high priority for South Africa and partners in Africa, with several astronomy workshops and training programs catering to different audiences. These efforts in human capacity development are now starting to bear fruit.

India has a long history in astronomy which finds pride of place in the nation along with its remarkable space sector. The country has several major astronomy instruments and is part of many international consortia, similar to South Africa. Astronomy is represented across multiple universities and research centres across India. Astronomers from both countries work together through consortium projects as well as research collaborations. And more exchanges are taking place via collaborations such as BRICS.

Astronomy holds a special place in both countries, relative to other science and research investments. Astronomy projects are well publicised and known among the general public. But funding remains a challenge in both India and South Africa.

Do you see any similarities and synergies?

Astronomy for development is critical in both countries. One area of possible synergy is in astrotourism. South Africa recently published its draft astrotourism strategy while India established a dark sky reserve around an observatory. Both countries have massive rural populations, and large swathes of less-developed regions which could directly benefit from astrotourism.

In your opinion, what is the biggest challenge for astronomy in society globally?

Astronomy enthralls most people, but is not perceived as relevant. As long as astronomy remains niche in the public mind, engagement will be difficult and costly. It also necessitates constant justification of any public investment in the field.

Although astronomy is deep-rooted in our psyche, even the largest campaigns reach only a couple of million people, barely a fraction of the global population. For comparison, the “Avengers: Endgame” movie is estimated to have been watched by hundreds of millions. It is true that astronomy does not have the same level of marketing resources, but the disparity is stark when you consider that most astronomy activities are free or low cost, much more accessible, and possibly appealing to a wider audience.

My own view is that astronomy is perceived as complex or intimidating, and not relatable by most people. It is mainly seen to be an educational tool, and sometimes of entertainment value, and left to the select few professionals in the field. But the larger potential and relevance of astronomy is missed. This widespread disconnect with society is a major barrier for any astronomy project, thereby limiting our potential.

What are most exciting and most difficult parts in your job?

The OAD is a great place for brainstorming and idea generation as well as a hub of action. We are encouraged to be creative and anyone is able to pitch a new idea or a different way of doing things. We took this approach to the extreme for the IAU GA, and ended up developing completely new ways of hybrid conferencing.

Telling people no is the most difficult part of the job. Every year we receive around 100 proposals but we are, unfortunately, only able to fund ~15%. In the past, we had to decline some amazing proposals due to our funding limitations. Since there are few such funding opportunities, and almost none in some countries, some ideas don’t end up being realised. Knowing that a ‘no’ from the OAD could mean the project might never get implemented makes the decision even more difficult.

Are there authors, books, people or special events that have influenced you along your journey?

Like many, I was and still am influenced by the words of astronomer Carl Sagan, both via his books and TV appearances. I have also been shaped by my time in South Africa and at the IAU OAD. You will find some of the most kind and empathetic people in South Africa despite its history and extreme challenges, or maybe because of it.

The OAD in turn has cultivated a spirit of collaboration, respect, and humanity that is not very common in a working space. More than anything, I have learned that our achievements mean very little if we lose our humanity.

Add Comment